Internal documents contradict claims from the CDC, which refused to explain the discrepancy.

As Hubert Humphrey prepared to mount the rostrum of the International Amphitheater in Chicago at 10 p.m. on Aug. 29, 1968 to deliver his address accepting the Democratic nomination for president, the television networks abruptly cut away to footage of National Guardsmen in armored jeeps firing tear gas and swinging their billy clubs at Vietnam War protesters in Grant Park across town. The video lasted 17 minutes—an eternity both for the 89 million Americans watching the broadcast and for Humphrey’s candidacy. The Democratic convention was a catastrophe for Humphrey and for a nation that it left more polarized than ever. The only beneficiary was the Republican candidate, Richard Nixon.

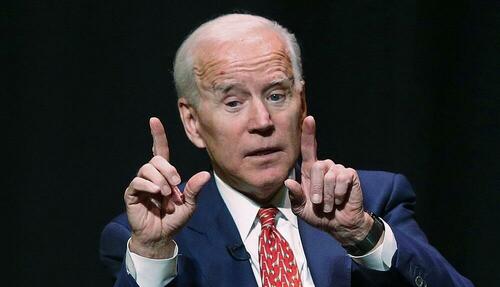

It is suddenly all too imaginable that the Democrats will re-enact that drama, with President Biden as Humphrey, today’s antiwar protesters standing in for yesterday’s and a Democratic convention looming in…Chicago. Of course Humphrey, as Lyndon Johnson’s vice president, was helpless to bring the Vietnam War to an end, while President Biden has ways to pressure Israel to end the war in Gaza or at least reduce the violence. But if he fails, Democrats will have good reason to worry about 1968 redux and to ask themselves what they can do to mitigate the worst.

The conventional wisdom of 1968 was that Humphrey lost to Nixon because he couldn’t find the courage to break with Johnson on a war that a majority of Americans had come to oppose. That’s almost certainly wrong: Disaffected liberals ultimately came back, but disaffected blue-collar voters, who largely supported the war and abhorred the chaos in the streets, defected to Nixon or to George Wallace. (A Harris Poll found that two-thirds of respondents supported the Chicago cops’ tactics.) Humphrey carried the liberal Northeast (save New Jersey) but lost Illinois, Ohio and Pennsylvania. The shrunken Democratic base that emerged from the election is very much the one the party relies on today: Blacks and well-educated white liberals. Nixon’s victory over George McGovern in 1972 further weakened the party’s hold on the white working class, a trend that has continued unabated ever since.

In the weeks before the convention, Humphrey’s conservative advisers told him to stick with the president on Vietnam and come down hard on the kids in the streets. Humphrey refused to do so, not only because it would have been cynical but because it wouldn’t have solved his dilemma: While he needed to keep the votes to his right, he couldn’t afford to lose the energy and idealism to his left. This one-time liberal hero found it unbearable that the most passionate elements of the party hated him. Humphrey knew that without the activists and the antiwar crowd he would just be the candidate of big labor and the party bosses.

In reading through Humphrey’s records, I found a memo from a campaign aide suggesting that the candidate try to defuse the anger by meeting with Rennie Davis, a leading organizer of the protest movement. Routed to campaign manager Larry O’Brien, the memo came back with a note: “Larry looked at this and said to skip it.” Humphrey could scarcely have defused the antiwar effort by having coffee with Rennie Davis, but he could have found ways of acknowledging the depth of the protesters’ anger, and even of saluting their moral commitment, without taking their side. Indeed, it was only when Humphrey finally broke with Johnson on the war in a Sept. 30 speech that young people and liberals rallied to his side and the campaign caught fire.

This is a painfully familiar dilemma for President Biden, another moderate liberal in an age of extremism. Biden is also leaking support from both flanks of his party, but he is far more endangered by erosion among non-college-educated voters on the party’s right. He, too, is blamed for an unpopular war, yet, like Humphrey, is reluctant to make a sharp break both as a matter of personal conviction and as a political calculation, since so many Americans who are not young and not liberal actually support the war. But a Democratic Party shorn of its progressive wing is not only smaller but even more devitalized than it feels now.